Devon Walks - Tavistock Canal

In 20 years of writing about walks here in the South West I’ve come to realise there are certain types of hike that tick more boxes than most, but that these sometimes come under headings that might not be obvious to, say, a publisher. And so, while there are hundreds of guidebooks with names like Pub Walks of Borsetshire, there are very few with titles like Secret Walks from Town Centres.

Which is a pity because it is potentially a winning recipe. I’m talking about the kind of walk that allows you to be at the busy heart of some well known urban conclave one minute, and out into some deeply peaceful rural setting the next. Well, in 15 or 20 minutes perhaps.

I was musing upon this one day while researching this feature which does indeed include a remarkable walk, but which is really about a community effort to reinstate a number of poetry installations along the banks of a historic canal.

It was my old friend, the poet James Crowden, who brought the story to my attention - because he was the man who, seven years ago, inspired a group of students from the Tavistock Community College to create some remarkable snippets of poetry focusing on the historic canal which passes directly past their school’s playing fields.

The project was originally funded by the local Tamar Valley AONB team and the words created by the students were painted on various bridges or other fixtures along a publicly accessible walk which follows two-and-a-half of the canal’s four-and-a-half miles.

More about the history of the canal in a minute. I found myself walking along its towpath recently with some people who are working to have the poetry reinstated for a third time.

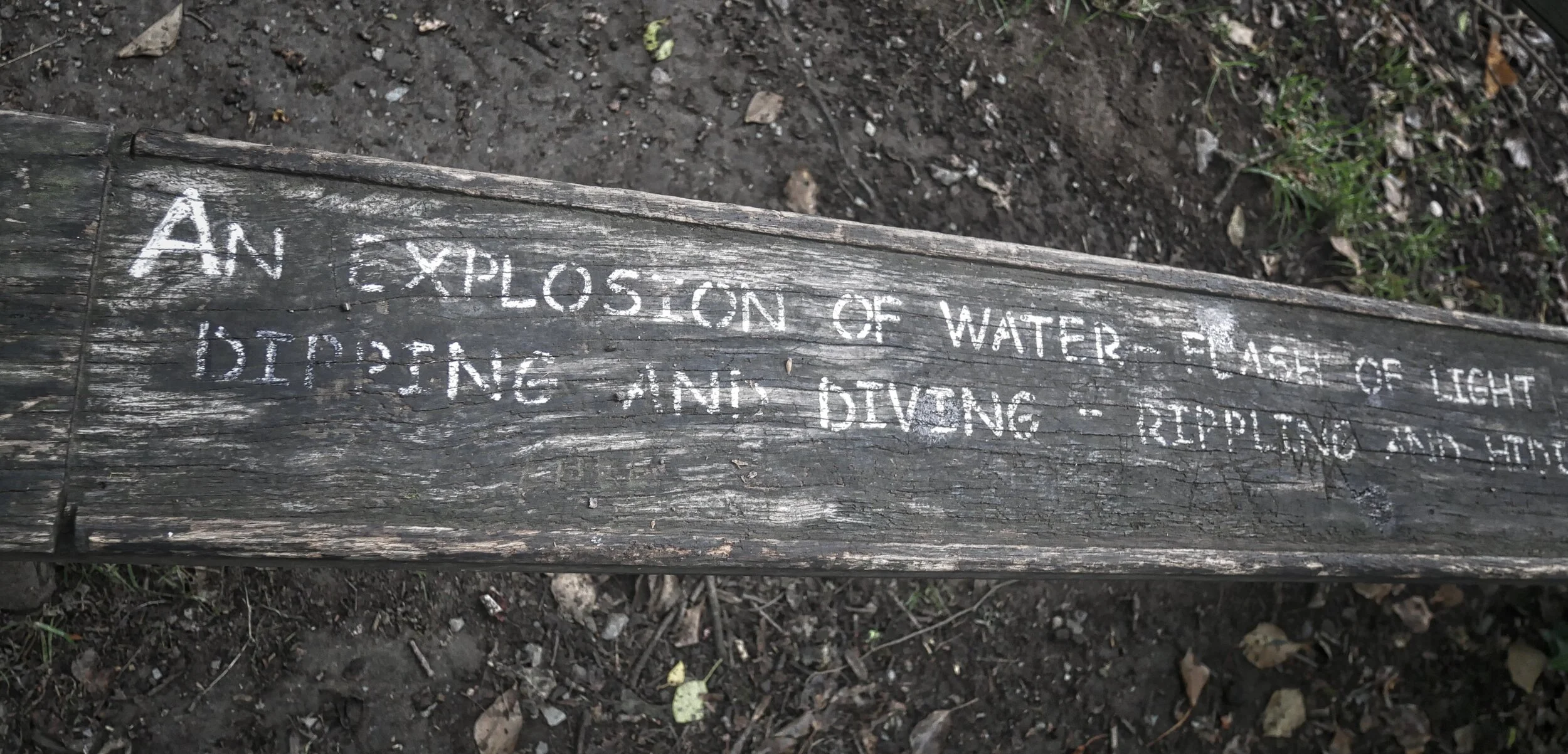

It was a couple of years ago that local resident Jane Miller spent six months renewing the installations which can be seen at nine locations along the canal walk. The walk follows the canal to the end of the public path at Lumburn, a distance of about 2.5miles, where James’s poem ‘Endgame’ can be read. The lines of verse have been written on different structures, (benches, wooden slabs), and vary in length from one line to several couplets.

The trouble is, the painted words have - for the second time - either been weathered away or they were printed on metal fixtures which have been stolen.

Jane told me: “It was really nice to have the poetry along a walk, but it had become very faded and indecipherable so I decided I’d like to renovate it. So I got in touch with James Crowden and various other people, raised some money, and reinstated it. Now it needs doing again in a more permanent way.”

As we prepared to walk along the towpath, James explained: “I grew up in Tavistock so I knew the canal very well indeed. It’s not really my poetry - I did two different workshops with the children of Tavistcok College and they produced some really fantastic stuff. We then worked on an edited version of that. There was money from the Tamar Valley AONB at the time.

“Then later, off her own back, Jane decided she wanted it reinstated - and we are possibly doing it a third time now.”

At this point we were joined by local historian Simon Dell, who has written a guide book on the canal and who told us something about the history of this remarkable waterway…

“It was constructed by John Taylor - the 19-year-old mine-captain over at Wheal Friendship Mine at Mary Tavy. He realised that the transportation of copper ore out to the rest of the world - down through Morwellham - was impossible along the primitive trackways that existed. So he built a canal which goes from Tavistock all the way along the four-and-half miles to Morwellham Port (on the River Tamar).

“Approximately an hour away from town the canal goes into a tunnel which is not open to the public - but there is a lovely footpath all the way out of Tavistock, past Crowndale, the birthplace of Sir Francis Drake. We’ll go out along there beneath the old London and Southern Railway Line that we are hoping may one day be reinstated - and we will go out to Lumburn. It is a fantastic stroll.

“The canal is about eight-feet-wide and, at its deepest, it’s only about three feet. That is because the canal barges had a very shallow draft,” explained Simon, as we began our walk from the centre of town. “And this is a flowing canal - but it’s only what they call a ‘sweetening flow’. They close off the canal if the river is really low because the Tavy’s flow needs to be maintained.

“The tub-boats were 40-feet-long and about four-feet-wide with a shallow draft of two-feet - and they would carry eight tons. It took one horse to tow them down full of ore with the flow, and two horses to tow them back up. They brought back coal, lime, wheat and grain. As we are walking we will come across the old town grain store.”

We did indeed. It was remarkable to see how low the tunnel beneath the grain store was. “The men would have had to croopy down (squat) because the grain was brought up on the empty barges and underneath the building there were hatchways. The barges would stop and the grain would be lifted into the grain store for the town.”

We walked on down the canal to the edge of town and so could see Tavistock Community College at a point where James read out one of the first of the poetry installations from words carved into the parapet of a bridge…

“The heavy weight of copper ore,

slowly being pulled,

by man and beast in harmony,

moves so much slower than the world,

as if encased in a different time.”

Jane commented: “When we were reinstating the poems the first time around we went to the college and James spent the day getting the children to write a new poem. They were mainly girls - mainly self-conscious - and we walked along the canal in pouring rain. Over the day, James extracted from first a word, then a phrase, then a sentence… And he put this together."

James explained his technique when leading poetry workshops - a job he has done many times over the years in all manner of locations - from primary schools to prisons…

“First you have to read out some poetry of your own, make them feel at home and - in a phrase - give them permission. The only trick I have - if it is a trick - is to make it a group activity, so they are not on their own. They are still in their own thoughts, of course - but I get them to read out small bits several times down the journey. And by the time you get to the third or fourth session they are writing whole poems because they are feeling at home with expressing it within that group.

“I’ve done that in prisons with prisoners and it is really interesting how it works.”

At this point we came across yet another poem along what really is a most beautiful of walks…

“There’s a wonderful line here which I’ve forgotten,” said James.

“Suitcase of leaves,

It’s only luggage,

The water meanders

On its purposeful journey.”

As we walked on along the towpath, past Sir Francis Drake’s birthplace and beneath the mighty rail viaduct, Simon told me: “The canal has a four-foot fall in four-and-a-half miles. One foot per mile. How about that?”

It was, indeed, amazing to see the rate of flow that is created by such a shallow drop of just one foot in a mile… “It was just enough to allow a horse to be able to easily pull a fully laden ore boat down, and it took tow horses to two it back,” said Simon. “The route we are following is actually the ancient route of the Crowndale Mine leat - so Taylor didn’t reinvent the wheel, he followed an existing route for the first mile.”

Eventually, we neared the end of the public-right-of-way which falls short of the tunnel that takes the canal underneath a range of steep-sided hills.

“The tunnel was at one time the deepest in Europe below ground level - 350 feet below Morwell Down,” Simon explained. “Then, where it exits, it goes down a 300 foot inclined-plane to the port of Morwelham.

“There is now a hydroelectric station on the banks of the River Tamar and so this is not used as a transportation canal nowadays, but used to provide motive power to the power station, which dates back to 1934. The canal flows into a reservoir, then down a tube to the power station, then the water flows into the River Tamar. It creates a significant amount of electricity - it is a significant income generator for the South West Water Authority which owns the canal.”

At the end of the publicly accessible towpath, walkers can turn right and continue along a path which follows what used to be a kind of branch-line…

"The collateral cut went up to Mill Hill Quarries,” said Simon. “It was constructed in 1817 after this canal was flowing, but unfortunately it only last four or five years before they filled it in because there wasn’t enough water. They built a horse-drawn tramway on the top so the slate from the quarries could be brought here, loaded onto barges and taken to Morwelham for export. The quarries are still operating and it’s a major local employer.”

As we took a rest on a bench at the place where public access ends, Jane told me: “The poems are painted on so of course they weather away - and some have already becoming weathered down after just two years. So what we’d like to do is replace them with hardwood that is routed, and that would be much more permanent.

“The poetry, I think, is extraordinarily effective and moving. The people who wrote it were Year 7 students aged 11 and 12 - and they produced really thoughtful and thought provoking words. It is worth keeping - I don’t think it should be let go.”

James agreed that it would be good to see the words carved in wooden installations: “What is important is that these are local words from a local place - and, like with local food, you can’t get better than that,” he said.

Jane Millar points to a missing poetry plaque

“The students are reflecting what they have observed and it has a communal worth - and that is what is so interesting. I’m really pleased that Jane and her friends are getting involved for what is a third time now just to evolve a way in which it will work for longer.

“The children who have written this will grow up and they will still remember it if it’s here - and they may bring their children. That’s the interesting thing. I have found this with other projects - people remember them way beyond the time when they are created. It’s not like a normal school lesson.”

Next to the bench at the end of the walk there is an installation that represents the tunnel - and in the last arch is the poem called Endgame which was written by James himself - and which is a fine and eloquent way to end this article…

“From here the water slides

Under the hill into the slender dark

Engineer’s precision masterminding the flow

Import-export,

Tamar calling.

Inclined plain beckons the ore,

Morwelham high and dry,

The canal’s very own hydro powering the current

Tamar Calling.

Welsh coal, poled through the tunnel,

Ore from Wheal Betsy and Wheal Friendship,

Crowndale and Wheal Creber,

Saltridge Consols and Wheal Franco,

On the slate, Mill Hill cut,

Limestone and miscellaneous fripperies,

A narrow corridor sunk under the hill,

Coming out into the light

Taylor-made.”

If you’d like to know more about the canal and about the walks you can do around it, Simon Dell has written a local guide called Tavistock Canal Walks.